Where Are the Serial Numbers Located on the Oliver 88

1937-1948 era Oliver Model 80 agricultural tractor

The Oliver Farm Equipment Company was an American farm equipment manufacturer from the 20th century. It was formed as a result of a 1929 merger of four companies:[1] : 5 the Solid ground Seeding Auto Company of Richmond, Indiana; Oliver Chilled Cover Works of South Crim, Indiana; Hart-Parr Tractor Caller of Carolus City, Iowa; and Nichols and Shepard Company of Battle Creek, Michigan.

On November 1, 1960, the White Motorial Corporation of President Cleveland, Ohio, purchased the Oliver Farm Equipment Company.[1] : 123

Merger [edit]

Four companies merged on April 1, 1929, to take shape the Oliver Farm Equipment Company: The Oliver Chilled Plow Ship's company, dating from 1855; the Hart-Parr Tractor Company from 1897, and the American Seeding Machine Companion and Nichols and Shepard Company, some dating from 1848.

By 1929, all of these companies had reached a point where continuing operations independently would non be feasible. For nigh of them, the market had or s time earlier reached a saturation point, and in more or less instances, their machines were dated and rapidly approaching obsolescence. By uniting their various and somewhat diverse product lines into a single company, Oliver Farm Equipment immediately became a full-line manufacturer.

Merged companies [edit]

American Seeding Simple machine Company [edit]

"Oliver Superior" ingrain and fertiliser drill

The American Seeding Machine Company was organized in 1903 from the a merger of seven different manufacturers of grain drills, corn planters and other "seeding machines." The leading corporate component part among the vii merged companies was the Superior Drill Company of Springfield, Ohio.[2] : 189 Accordingly, the American Seeding Machine Company established its organized headquarters at Springfield in the facilities erst operated by the Shining Drill Company.[2] : 189 Other companies which settled the 1903 merger include P. P. Mast and Society (est. 1856), Hoosier Practice Company (est. 1857), the Empire Practice Company, and Bickford & Huffman. The Preeminent Practise Company name lived on for many years following the merger that created Oliver, in the "Joseph Oliver Superior" line of seeding drills and related equipment.

Oliver Chilled Plow Works [edit]

Epistle of James Oliver started the Oliver Chilled Plough Works in 1853[2] : 107 In Mishawaka, Indiana where he worked in a foundry. He afterwards bought into an already present small foundry in South Bend, Ind..[3] Plows with ramble Fe bottoms and moldboards had been successfully secondhand by farmers and planters in the eastern states of the United States since the time of Thomas Jefferson.[1] : 107–108 Withal, in the sticky soils of ND and various other portions of the Midwest, the cast Fe plows would non "scour"; that is, the sticky soil would stick to the plow, disrupting the perio of soil over the plow's control surface, devising plowing out. Thus, when settlement of North America moved finished the Allegheny Mountains into the Midwest, in that location was a need for a new plow that would follow able to scour in the soils of the Middle west. To allow a cast iron bottom to purge in steamy soil, single methods of heat treating for creating a hardened surface on the metal plow bottom had been attempted. All of these processes failed because the hard surface created was same thin and would soon wear out through to the soft iron under the passion-treated come up. James Oliver developed his sand casting process to include rapid chilling of the molten iron come near the outside surface of the molding, which resulted in a lowermost that had a thick hardened shallow with far greater wearability than competing plow bottoms.

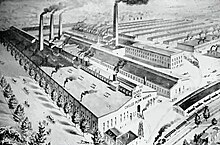

The catch to the Oliver Chilled Plow Works in South Bend, Indiana, c. 1880.

Another problem common to cast iron out handle bottoms was the lack of wisdom and uniformity in the metal's molecular structure, which meant that some cast robust bottoms would have soft floater in the set surface, reducing the wearability of the plow penetrate. Improvements made by James Oliver to his casting process also overcame this trouble.[1] : 107 Consequently, on June 30, 1857, James Oliver obtained his first apparent from the United States for his chilled plow shares[4] and in Feb 1869, he obtained some other patent for his process. What Oliver accomplished by this invention is sometimes referred to as chill hardening, OR simply chilling. The purpose of chilling is to produce an super hard and durable exterior of the object. This is done by including "chills", pieces of bimetal, into the moxie work, such that when the molten Fe is poured into the mold, the portion next to the chill cools rapidly, hardening in a way akin to extinction. This chilled area forms the exterior of the plowpoint. This metal cools many quickly than the bronze which forms the other portion of the ploughshare, and effectively becomes casing hardened. Also, the vapors which arise as the molten metal comes in contract with the form are expelled done a spout. Had these vapors been trapped in the mould, they would have caused impurities and would have weakened the plowpoint at the place where it should take been the hardest. To harden the plowpoints, Oliver staged his moulding apparatus in such manner that the surface of the frisson was in a position so that the melted metal first came into touch with the chill at the edge of the plowshare. This insured a hard plow cutting item.[5]

An artist's conception drawing of an aerial view of the Oliver Chilled Plow Works, South Bend, Hoosier State, c.1900.

Thusly, James Oliver's chilled handle bottom became a practical success and on July 22, 1868, the Joseph Oliver's business was incorporated as the South Bend Cast-iron Works. In 1871, the company sold 1,500 plows per year. By 1874 this figure had increased to 17,000 plows a year.[1] : 107 At the sentence of death of James Oliver in 1908, the keep company had again changed name calling to the Oliver Chilled Plow Workings. and their manufactory site in South Bend, Indiana covered 58 landed estate (230,000 m2) with 25 of those demesne nether roof.[1] : 107 In January 1885, the plant's for the most part Polish workers went on strike in protestation of cuts to wages and hours in response to a binge of descent.[6] Veterans of the Civil War with fixed bayonets finally ejected the strikers from the premises.[7] The ownership considered leaving South Bend in the wake of the destruction of parts of the establish, with newspapers stating that they feared "the Collectivist influences operating among the foreign elements at Southward Bend...probably emanating from Chicago."[8] Many workers employed in handle factories died from grindstone pulmonary tuberculosis. This is the solution of the scatter from emery wheels and grindstone in the attrition and shining rooms. "In Dixieland Bend, the 'grinder' is either a Pole or a Belgian; sol when he dies, society knows nonentity about it." [9] Upon the death of his father in 1908, Joseph D. Oliver, the merely Logos of James I and Susan (Doty) Oliver took over the management of the Oliver Chilled Plow Works. By 1910, the company was manufacturing a wide variety of farm tillage implements in addition to the chilled handle. Production had reached the point that, in 1910, the fellowship purchased over 40,000 tons of pig smoothing iron unequaled.[1] : 107

Hart-Parr Gas Engine Company [edit]

Hart-Parr 30-60 "Old Time-tested"

Charles Walter Hart was born at Charles Urban center, Iowa in 1872. At the age of twenty dollar bill, he transferred from Iowa State College of Agriculture and Automatic Liberal arts, to the University of Wisconsin–James Madison.[1] : 54 It was present that he met Charles H. Parr, and the two inexperient men quickly became friends. Together they worked on their Unscheduled Honours Thesis and from that thesis they built trio working interior combustion engines right there on the campus at Madison.[10] : 24

Following their graduation from the University of Wisconsin in 1897, Hart and Parr deepened $3000 in capital and trumpet-shaped the Hart-Parr Gasolene Engine Fellowship.[10] : 24 Towards the end of 1899, Charles Stag paid a gossip to his parents in Charles Urban center, Iowa. He complained to his founding father that growing funds could not be found for his tractor project. "At that place's money around here that might be interested," replied the older Hart, admitting for the first time that his Word's aspiration was not foolery. They then set up another investor in Charles D. Ellis, a local attorney, who invested with $50,000 in additional capital.[10] : 24–25

In 1900, as the locomotive business expanded, Hart and Parr decided to move their company from Madison to Charles City. Hart-Parr Company was incorporated on June 12, 1901, at Charles City, Iowa. Dry land was broken for the new factory on July 5 that year. Aside the following December, the Hart-Parr Company was now ready to do business, and had an authorized capitalization of $100,000.

Hart-Parr number 1 was completed in 1902. Customers did not immediately beat the proverbial path. However, Moss Hart-Catherine Parr was able to field unitary salesman to run demonstrations at county fairs and new events. Hart was patient. "We can't force it," He said. "We have got to let it simmer into the securities industry."

Little by little, the Hart-Parrs began to gather defenders. Some of the first tractors delivered were gaining a reputation of usefulness that far surpassed that of the steamers.

W.H. Williams, Gross revenue Handler in 1907, decided the wrangle "adhesive friction engine" were vague and too long to be used in compact releases, indeed he coined the word "Tractor", a combination of the wrangle "traction" and "power", instead. For this understanding, and because the Charlemagne City plant was the first to be continuously and alone used for tractor production, Hart-Parr often used the slogan "Founders of the Tractor Industry" in their advertising.[11] [12] [13]

Nichols and Shepard Company [edit out]

In 1848, John Nichols opened a blacksmith shop in Battle Creek, Michigan.[10] : 34 In the blacksmith shop, John Nichols began making various grow tools for local farmers. He built his first thresher/separator in 1852.[10] : 34 The business was self-made from the start, so successful that some clip in the 1850s he took on a partner by the name of Saint David Shepard.[10] : 34 Put together they formed a partnership known as Nichols, Shepard and Company which manufactured raise machinery, steamer engines and mill machinery.[1] : 92–93 The first thresher/separator of small grains (largely wheat and oats) was developed in about 1831 by the Pitts brothers—Hiram and John Pitts of Buffalo, Unprecedented York.[2] : 403 Nonetheless, this early thresher, called the "ground hog," was quite unlike the conventional fox shark/separators that developed since that clock. For instance, the ground hogg's separating unit was mostly a slatted apron which pulled the grain across a screen out.[1] : 92 John Nichols and David Shepard realized that the forestage style separator was non a technology that was going to solve. Consequently, in 1857, the Nichols and Shepard Company developed the ordinal "vibrator" separating unit for the small grain thresher.[1] : 92 This vibrator-style of extractor soon became universally adopted by all opposite thresher/separator manufacturers. The Nichols and Shepard Company received a patent from the Consolidated States government for their "Vibrator" food grain separator on January 7, 1862.[1] : 92 The caller besides obtained a number of new patents for else advances in the thresher/separator technology, for freehand improvements in steam engine traction technology.[1] : 92 During the 1920s, the Nichols and Shepard Company industrial a successfully functioning corn selector. Following the acquisition of the Nichols and Shepard Companion by the Oliver company. This Indian corn chooser became the direct ancestor of the famous Oliver cornpicker.[1] : 143

Later acquisitions [edit]

For the first couple of eld, the tractors carried the Oliver-Lorenz Milton Hart-Parr designation, but the Hart-Parr essence soon disappeared, just as an entirely refreshing line of purely Oliver tractors successful their appearance.

McKenzie Manufacturing Party [cut]

Following the 1929 merger of the four companies into the Oliver Farm Equipment Company, several other firm acquisitions were made by the new company over a period of years. The initiative of these post-merger acquisitions occurred a mere year later, in 1930, when the Oliver Farm Equipment Company purchased the McKenzie Manufacturing Company of La Crosse, Wisconsin.[1] : 5, 123 The McKenzie Manufacturing Company was a leading maker of potato planting and potato harvesting equipment.[1] : 123 Acquisition of the McKenzie Company broadened the line of farm equipment offered by Oliver to include potato diggers which were then sold-out under the "Oliver" name. However, favorable the 1930 amalgamation production of the "Oliver" potato diggers moved retired of La Crosse, Wisconsin to Chicago, Illinois.[2] : 357

Ann Arbor Agricultural Political machine Troupe [edit]

In 1943, the Oliver Farm Equipment Company purchased the Ann Arbor Cultivation Machine Company of Ann Arbor, Michigan. Founded in 1885, the Ann Arbor Agricultural Machine Company became the leading manufacturer of "hay presses" or stationary balers.

Cleveland Tractor Company [cut]

The Cleveland Tractor Company became a part of the Oliver kin in 1944. At the October 3, 1944 stockholders meeting, with approval of the stockholders, the corporate name was changed to "The Oliver Corporation".[14] Crawler tractor production ended at Charles II City in 1965.

A.B. Farquhar Fellowship [edit]

In 1952 the A.B. Farquhar Company was oversubscribed to the Oliver Corporation. Based in York, Pennsylvania, in the 1850s as W.W. Dingee & Co, in 1861 young man of affairs Arthur Briggs Farquhar bought the business and enlarged it during the Civil War every bit the Pennsylvania Agricultural Works. In 1889, the A. B. Farquhar Keep company began edifice threshing machines and another farm machinery. Later, the accompany started the yield of cultivators for farm use (especially Solanum tuberosum harvesting equipment). Farquhar produced roughly steam engines untimely so moved onto the production of traction engines.

Product development [edit]

Crawlers [edit]

In 1944 Joseph Oliver acquired the Cleveland Tractor Company (Cletrac). They continued output of the existing Cletrac HG model until 1951. The agricultural Cletrac Hydrargyrum gradually evolved into the more industrial Oliver OC-3 which was produced from 1951 through 1957.

In 1956 Oliver proclaimed the slimly bigger OC-4 with a four-piston chamber Herakles IXB3 engine. In late 1957 (diesel) and early 1958 (gas) OC-4's came equipped with 3 cylinder Hercules 130 engines. All but noticeable was the change to a 'beefier' more industrial front grill. In 1962 at the parvenue Charles Metropolis, Iowa toady yield line, the last incarnation of the OC-4 was produced. It was a sturdier industrial model named the Series B. They were powered with the Saami 3 cylinder Herakles GO-130 and DD-130 engines of the mid-serial models. The OC-4 product line was discontinued in 1965.

Oliver also produced larger crawlers: the OC-6 from 1953 to 1960; the OC-9 from 1959 to 1965; the OC-12 from 1954 to 1961; and the OC-15 and the large OC-18.

All crawler production was halted in 1965.

Tractors [edit]

1956 Oliver Super 55 Diesel

In 1948, Oliver was set with an entirely novel line of tractors. These were built over the successes of the past, including the Joseph Oliver 60, 70, and 80 tractors.

The latter was even made-up with a diesel, although very few were sold. However, in the 1950s, Oliver was an industry leader done their advancement of Diesel power. Joseph Oliver LED the industry in the sale of Diesel tractors for several age.

The King Olive 66, 77 and 88 tractors of the 1948 to 1954 period, marked an entirely new series of Fleetline models. The 77 and 88 could be bought with either gasolene or diesel engines. During 1954, the company upgraded these tractors with the new "Super" series models, and added the Oliver Super 55. Information technology was the company's first compact utility tractor.

In 1958, Oliver began marketing the new 660, 770, 880, 990, and other new models.

Non-agricultural products [edit]

During the war eld of the 1940s King Olive Corporation expanded rapidly into non-agricultural production, most notably in the vindication sector. By 1947, the Oliver Corporation employed 9,000 with 37% of Oliver's output for defense contracts. Product lines enclosed graders, forklifts, road rollers, crawlers, and power units incorporated into products by other companies.

Oliver also built plane fuselages for Boeing Rb-47E Reconnaissance mission planes at a Fight Creek, Michigan aviation sectionalisation localise up only for defense contracts. The Charles City, IA plant assembled transmissions for the 25-ton Grus carriers and built and assembled 106 mm recoilless rifle grease-gun mounts for the Army. The Cleveland, Ohio plant built the MG-1 red worm for the Army as well As tankful parts. The Gilroy, California plant produced the 76 mm guns for the John Walker Bulldog storage tank. The Shelbyville, Ohio plant built 155 mm Howitzer gun parts.

Acquisition aside White Motor Tummy [edit]

Oliver Corporation [edit]

White Causative Corporation of Cleveland, Ohio had a extendible chronicle of truck manufacturing. On November 1, 1960, White Centrifugal nonheritable Oliver, changed the name to Oliver Potbelly, and made it a all owned, separately operating subsidiary of the White Motor Corporation.[14] : 154

Further mergers, acquisitions, and branding [edit]

White also acquired Cockshutt Farm Equipment of Canada in February 1962, and it was made a subsidiary of Oliver Corporation. Cockshutt had also previously, in 1928, marketed tractors successful by Hart-Catherine Parr, and again from 1934 through and through the late 1940s it marketed tractors made by Oliver, solely dynamic the paint color to Bolshevik, and changing the name tags to Cockshutt. Minneapolis-Moline became a wholly owned subsidiary of White Motor Corp in 1963. The Cockshutt and Minneapolis-Moline lines were blended into that of Oliver until there was nearly nobelium difference between them.

In 1960, the new four-digit tractor models appeared. Among them were the 1600, 1800 and 1900 models. In 1969 White Motor Corporation formed White Farm Equipment Company, almost in real time after a transitional period when virtually identical tractors and combines were marketed below different trade names. A couple of models were sold as Oliver, Minneapolis, or Cockshutt, the major difference being the paint colouring material. As the dealings continuing, the White name was progressively practical to the tractor line, with the Joseph Oliver 2255, too better-known as the White 2255, being the last strictly "King Olive" tractor. With the introduction of the Ashen 4-150 Field Boss in 1974, the White name would be used, henceforth to the exclusion of completely others.

White Motor Corporation shut down the innovational Oliver Chilled Plow Works factory (factory no. 1) in 1985. The Oliver buildings remained empty until 2002 when most were demolished to make room for an industrial park. The Oliver powerhouse is instantly restored and occupied by Rose Brick & Material.

FIAT tractors were marketed under the Oliver name in the mid 1970s, so much as the Oliver 1465 tractor. Oliver tractors with Order gages were available in 1970.

Today White is an AGCO brand. AGCO was formed in 1990 away late Deutz-Allis executives. The executives took over Deutz-Allis and then purchased the White tractor line in 1991. The White tractor line was produced by AGCO from 1991 through 2001 when the White line was merged with AGCO-Allis to make up the AGCO steel. The Colorless nominate continues on low-level AGCO with the White Planter division.

Legacy [edit out]

Many information almost Oliver Tractors nates represent found in Oliver Heritage Magazine.

References [cut]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Wendel, Charles H (1993). Oliver Hart-Parr. Osceola: Motorbooks International. ISBN9780879387426 . Retrieved 2018-12-07 .

- ^ a b c d e Wendel, Charles H (1997). Encyclopedia of American Farm Implements &adenosine monophosphate; Antiques. Iola WI: Krause Publications. ISBN9780873415071 . Retrieved 2018-12-07 .

- ^ Davis, H. Gail (1908). "The Storey of James Oliver and The Oliver Chilled Cover Works". 1. Personalized Papers compendium housed in the Archives of the Center for History, South Bend, Indiana: n/a. Archived from the original happening 2009-08-25.

- ^ United States Patent Office, Letters Letters patent No. 17694, "Improvement in Chilling Plowshares," June 30, 1857, to James Joseph Oliver and William Harvey Little.

- ^ Meikle, Douglas Laing, "James Joseph Oliver and the Oliver Chilled Plow Works." unpublished thesis, June, 1958. To learn more than about the Oliver company visit Oliver Chilled Plow Whole caboodle online history Archived 2009-08-25 at the Wayback Car

- ^ "Department of Labor Riots in March on". New York Multiplication. 14 Jan 1885.

- ^ "Labor Riots". Chicago Daily Tribune. 14 January 1885.

- ^ "Industrial News show". Chicago Daily Tribune. 20 February 1885.

- ^ Putnam, E H (July 1897). "Locomotive Firemen's Cartridge, Vol 23, No 1". Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Pripps, Robert N; Morland, Andrew (1994). Oliver Tractors. Motorbooks International. ISBN9780879388539 . Retrieved 2018-12-07 .

- ^ Finlay, Mark R. (1998). "Organization and Sales in the Heartland: a Manufacturing and Marketing History of the HartParr Company, 1901-1929". Chronological record of Iowa. State Diachronic Society of Iowa. 57 (4): 368. Interior:10.17077/0003-4827.10210. ISSN 0003-4827.

- ^ ""What does IT toll to plow an Akko?" [advertisement]". Diary of the American Bankers Tie-u. 12: 569. March 1920. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ ""The 1923 Stag-Parr Franchise Is Now Waiting" [advertisement]". Tractor and Gas Engine Review. 15: 13. October 1922. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ a b Culbertson, St. John D (2001). The Tractor Builders: The People Behind the Product of Hart-Parr/Oliver/Hot. Sunrise Hill Associates. Retrieved 2018-12-07 .

Further recital [edit]

- Oliver Tractor Data Bible, Motorbooks International, ISBN 978-0-7603-1083-0

- Classical Oliver Tractors: History, Models, Variations & Specifications 1855-1976, Motorbooks World, ISBN 978-0-7603-3199-6

Where Are the Serial Numbers Located on the Oliver 88

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Farm_Equipment_Company

0 Response to "Where Are the Serial Numbers Located on the Oliver 88"

Post a Comment